“You ain’t ever gonna amount to nothing.”

The first and last shots of “The Last Picture Show” are nearly identical. However, one is in reverse of the other. The movie marquee, once presenting the next showing, is now empty. After the last picture show has ended, there is not much left to do.

“The Last Picture Show” is such a vivid and knowledgeable portrayal of life in a small Texan town, that it would seem only to come from memory. Yet, director Peter Bogdanovich grew up in Kingston, New York, a place bearing no resemblance to rural Texas. He’s just that good of a filmmaker.

“The Last Picture Show” takes place in the fictional town of Anarene where football is king. This was long before “Friday Night Lights” ever came to be. Except here, none of the action takes place on the field, so glory is even harder to find.

From start to finish, “The Last Picture Show” is powered by the country tunes playing on everyone’s radios, primarily those of Hank Williams. In Anarene, which becomes a character itself, the greatest means of escape are the pool hall and the movie theater, especially that movie theater.

“The Last Picture Show” is a coming of age story in which the teenagers mature in a world that is not vibrant or cultured but instead rather bleak. Think the opposite of “American Graffiti.” As the film progresses, the culture diminishes more and more.

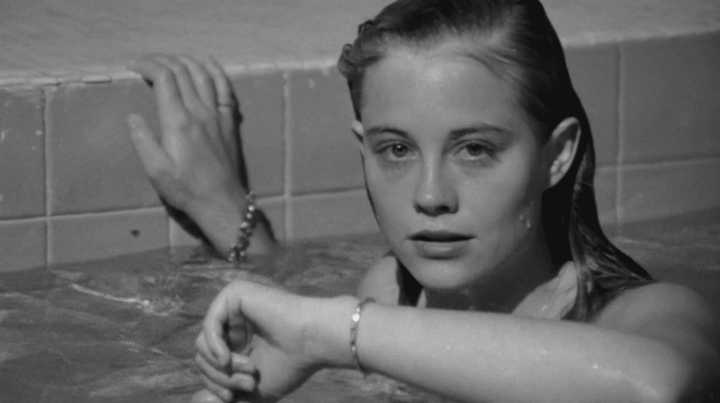

Instead of beginning with dialogue, “The Last Picture Show” starts off with the voices of disc jockeys and the music on the radio, perhaps the guiding voice of that generation. “The Last Picture Show” primarily follows the town’s star football players Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms) and Duane Jackson (Jeff Bridges). Sonny is kind and sensitive and in a relationship with a girl he does not love (Sharon Taggart). Their relationship will not last long. Duane, meanwhile, is confident, handsome and popular. He is first introduced while dating the beautiful Jacy Farrow (Cybil Shepard), Anarene’s equivalent of a movie star; a goddess wearing a scarf. In this drab setting, she is a human oasis.

Everything is in order until trouble comes during Christmas. After a holiday party, Sonny befriends and later has an affair with Ruth Popper (Cloris Leachman), his football coach’s wife. Ruth is miserable and despises her husband, but says she married him as a way of angering her parents. At a time when Hollywood favored youth rebellion against those who raised them, “The Last Picture Show” actually ends up being about a sacred respect for one’s elders. After all, everyone feels a need to rebel at one point or another.

That is what makes this film such a unique coming of age story: it is as much about the adults coming of age as it is about the kids. Coming of age, after all, is the act of discovering how one is supposed to act at a given time in their life. This act can occur more than once during one’s life.

The boys all end up vying for the affection of Jacy. This will eventually lead to each of their downfalls in one form or another. “The Last Picture Show” is less a story as a whole as it is a mosaic of little stories that fall together into a vivid, haunting, yet beautiful, whole. A road trip to Mexico that happens entirely offscreen and a pool hall given to Sonny in an inheritance are just two of the many threads tied together to make a whole. These events don’t need to be seen to have an impact. Watching “The Last Picture Show” brought to mind “On the Waterfront” and the disenfranchised teen rebels of “Rebel Without a Cause.”

Like these movies, “The Last Picture Show” also has a strong emphasis on the little moments that are often ignored in everyday life, yet can’t be ignored in front of a camera. Moments like the one in which Ruth struggles to get her shirt over her head felt improvised, like the moment in “On the Waterfront” when Terry (Marlon Brando) fiddles with Edie’s (Eva Marie Saint) glove. There is something funny and tender about moments like these that make the characters feel vulnerable and achingly real.

In a way, “The Last Picture Show” is not about the loss of innocence leading into the Korean War, but rather about how that innocence was never there to begin with. In Anarene, there is no difference between public and private lives. Jacy and Sonny’s impulse marriage begins partly because Jacy is bored, and partly because she wants to be the talk of the town.

“The Last Picture Show” contains some outstanding work from multiple actors who would continue to make a great impact on cinema. Bridges creates slick, confident characters who you always want to follow, no matter how egotistical or lazy they may be (the lazy part refers to a different movie, of course). So many sides of each character are seen and at one point or another, everyone of them seems either emotional or emotionless. For example, the film’s most indelible scene comes during skinny-dipping at rich boy Bobby’s (Gary Brockette) house. As Jacy gets up in front of everyone to undress, her insecurity is seen in the way she clumsily undresses, and at that moment she becomes more than a spoiled, shallow beauty queen. It might have helped that this was actually Shepard’s first nude scene. No one ever feels like they are acting: they seem to feel so free and comfortable in the skin of their characters that they are simply just existing in their roles. That also comes from the screenplay written by Bogdanovich and Larry McMurtry (who wrote the book that this film is based off of), which is so deeply invested in the local dialect. “The Last Picture Show” comes closer to achieving naturalism as most films ever will.

Despite the lack of culture in Anarene, the bits and pieces of cinema and music throughout aid in telling this story. Think about the clip of “Red River” shown in the theater. Bogdanovich chose it for a reason. Hank Williams’s “Why Don’t You Love Me” is a perfect sendoff song and it provides a melancholy epilogue about how hard it becomes to enjoy what we used to enjoy as we age. Not that the haunting last images needed to be explained, but the song certainly provides the right backdrop.

It would probably be hard to see something like “The Last Picture Show” get made nowadays. Bogdanovich has no shame ending without something uplifting to cling onto. However, that is what helps make the story feel so much more real, as it acknowledges that life doesn’t always end with a big, bright ribbon tied to it. Even the healing and uniting power of movies, which the boys depend on, can’t be relied on anymore, as the theater closes its doors. “The Last Picture Show” will remind you that sometimes closure is not the most rewarding way to end a movie.

Here’s an Idea Hollywood: A modern day update of “The Last Picture Show” about the closing of a small town video store. Boom. I expect to be paid now.