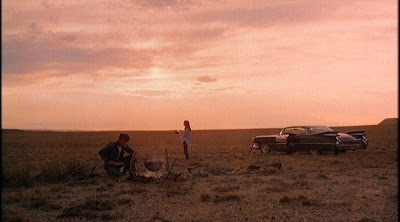

Watching a Terrence Malick film is like taking a stroll through nature. Or in the case of “Days of Heaven,” harvesting it, burning it, and possibly getting killed by it.

Watching a Terrence Malick film is like taking a stroll through nature. Or in the case of “Days of Heaven,” harvesting it, burning it, and possibly getting killed by it.

Watching a Terrence Malick film is like taking a stroll through nature. Or in the case of “Days of Heaven,” harvesting it, burning it, and possibly getting killed by it.

Watching a Terrence Malick film is like taking a stroll through nature. Or in the case of “Days of Heaven,” harvesting it, burning it, and possibly getting killed by it.

Unless you love, your life will flash by. Terrence Malick’s “The Tree of Life” is the most highly ambitious film to come out of this year, many past years, and many years in the future. It comes from what must have been years of obsessive thought about both life and film. Only someone this in love with the craft, and with nature, could make this film, and somehow make it masterful. “The Tree of Life” begins in a small Texas town in the 1950s, in what must be loosely based off of Malick’s own upbringing. Brad Pitt plays the tough patriarch of a family of three boys. Pitt, who is never given a first name, continually fights his wife (Jessica Chastain) over the best way to raise their family. Throughout the film, they explore loss of innocence and the possible meaning of life. Usually, trying to find the meaning of life is a cheap storytelling technique. But if you’re as good of a filmmaker as Malick is, the answer doesn’t come in one sentence. The film takes us from Texas to the cosmos to the creation of the life, and back again. Somewhere in between, an older version of one of the sons (Sean Penn), comes back to explore it all. The sum of “The Tree of Life” is nearly impossible to explain. After one viewing, any interpretation could be right. Malick’s latest is a reminder of his films from the past: it takes its precious time, and it is very quiet. “The Tree of Life” is reminiscent of a brief time when films told entire stories through images. Malick’s story, which covers basically the entirety of existence in just two and a half hours, manages to be the cinematic sequel to “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Like “2001,” “The Tree of Life” is nothing short of a cinematic opera. Malick, while echoing Kubrick, also does something that few filmmakers have done this well: capture the flawed beauty of nature. Light shining on a bed, tall grass being ruffled by human hands, and flies buzzing around a lake at dusk have never looked this stunning. He captures both the sights and sounds of the natural world to a perfectionist degree. This is naturalistic filmmaking at its finest. Through a camera lens, he encapsulates Thoreauvian philosophy. As a critic, it is important to try and avoid overanalyzing. However, for a film like “The Tree of Life,” overanalyzing is crucial. Through his film, Malick is trying to find more than just the meaning of life, because life doesn’t have just one meaning. “The Tree of Life” is about what is out there, and what brings us all together. Some might call Malick’s film a religious one. While religion seems to be a big factor, I would say that the film straddles the line between spirituality and atheism. It asks these essential questions: when it comes to dealing with the biggest questions in life, who (or what) do we turn to? Do we look to nature, the possibility of God, or our friends and family? No choice we make is a decent or right one, unless it is done out of some form of love. “The Tree of Life” is not a film that offers easy answers. Within a half hour, many people in the audience had walked out, something I haven’t witnessed since “A Serious Man.” After “The Tree of Life” ended, one woman remarked that the film was reminiscent of a bunch of Windows screen savers. A friend of mine compared it to the greatest “South Park” episode ever.

While both of these interpretations are funny, they do not do Malick’s film justice. The cinematography is the result of years of careful work, not stealing. Meanwhile, overanalyzing is the act of finding meaning in the meaningless. Malick surely had some deeper purpose in trying to discover how life exists and thrives.

“The Tree of Life” is hard to be in love with the first time around, but I feel a need to recommend it. I can’t get over the brilliant way in which Malick speeds up, and then slows down, the story at just the right moments. Many films made nowadays try to think up and balance big ideas, but few are ever this meditative.

“Badlands” just proved the impossible to me: an epic story can be told in under two hours. In fact, all you really need is 90 minutes. It may just be that Terrence Malick is one of the best, and definitely the briefest, epic storyteller.

“Badlands” just proved the impossible to me: an epic story can be told in under two hours. In fact, all you really need is 90 minutes. It may just be that Terrence Malick is one of the best, and definitely the briefest, epic storyteller.

![]() James Cameron only makes a movie every 10 or so years. But every time he does, he seems to rewrite the rules of filmmaking. With “Avatar,” James Cameron not only rewrote the rules, but opened a whole new book.

James Cameron only makes a movie every 10 or so years. But every time he does, he seems to rewrite the rules of filmmaking. With “Avatar,” James Cameron not only rewrote the rules, but opened a whole new book.

Of all of the stunning images from “Gangs of New York,” one that sticks out is a shot that starts off on street level, and continues to go higher and higher until the 19th Century style buildings become the shape of the island of Manhattan. Here is a city that, over the years, I’ve grown to know and love. Here it is, in a form like we’ve never seen before.

Of all of the stunning images from “Gangs of New York,” one that sticks out is a shot that starts off on street level, and continues to go higher and higher until the 19th Century style buildings become the shape of the island of Manhattan. Here is a city that, over the years, I’ve grown to know and love. Here it is, in a form like we’ve never seen before.